Want to listen to this blog instead?

Hit play!

Want to listen to this blog read by the author instead?

Hit play!

Does it matter if people think differently to us?

They say “to know science, is to love science” and I’ve recently realised I’m guilty as charged.

Working at science centres and public outreach events, I saw it was my job to communicate how “cool” science was. That way, the audience would think that as well.

The people I secretly dreaded being stuck in a conversation with though: the people who did not think like me. ‘Psuedosciencers’, if you will.

The intentionally unvaccinated, people who argued that human-caused climate change wasn’t real, those who genuinely believed in conspiracy theories.

I saw another part of my role as correcting the world’s misunderstandings, because their way of thinking and understanding science was clearly wrong.

But provided a different way of thinking does not harm anyone: does it matter? Is it important that I prove, like the youngest sibling that I am, that I’m right and they’re wrong until I’m blue in the face?

Or is it important that the people I interact with are citizens who participate in society are law-abiding, otherwise okay humans who have all their other eggs in their basket?

The house that science and values built

Science has built its own self-perpetuating mythos and sense of grandeur: science should be objective, free of values or any sort of humanity.

Turns out, science is anything but. It is a social construct and has flaws, because people are inherently flawed. And people have values, opinions, thoughts, feelings and things they care deeply about, which will ultimately ‘get in the way’ of sound, logical reasoning.

Social constructivism is all about how people build their worldview through their social and worldly experiences. Since being a health science professional in my mid-twenties, I had socially constructed a house made of science, my values, my identity, the way I perceived the world. I had freely drunk the scientific Kool-Aid, yet hadn’t taken the time to pause and think about the power and structure imbalances that had been built into the very system I so easily subscribed to.

How was clutching to my house of science any different from someone who had built theirs on seemingly shaky ground? And was it worth my time and energy trying to change their information bricks when their house was already built?

I’m wrong, you’re right

I don’t pretend to know the answers to inspire behaviour change (yet). But turns out, in wanting to change people’s minds before their behaviour, I was wrong too.

My house of science was under attack. I didn’t know that I was also attacking their house with fact bombing, the first (order) cardinal sin of science communication.

I wasn’t prepared to take on their worldview and take on new information, and ask the bigger question: why? Afterall, science communication breaks down not with the lack of knowledge, but when the practitioner fails to understand and speak to the core values of their audience. Or speaking to them with ‘their house’ in mind, say.

Instead, I should have been practicing the very thing that I think is cool about science: its curiosity about the world.

A chance to observe and ask questions of someone who does not think like me, precisely for that reason.

Does it matter that someone thought the Moon landing wasn’t real? Probably not.

Does it matter that the same person also likely paid their taxes, put a seatbelt on when driving, and wore sunscreen when they went to the beach? Probably.

Science isn’t perfect, but it’s the best system we have to understand our world.

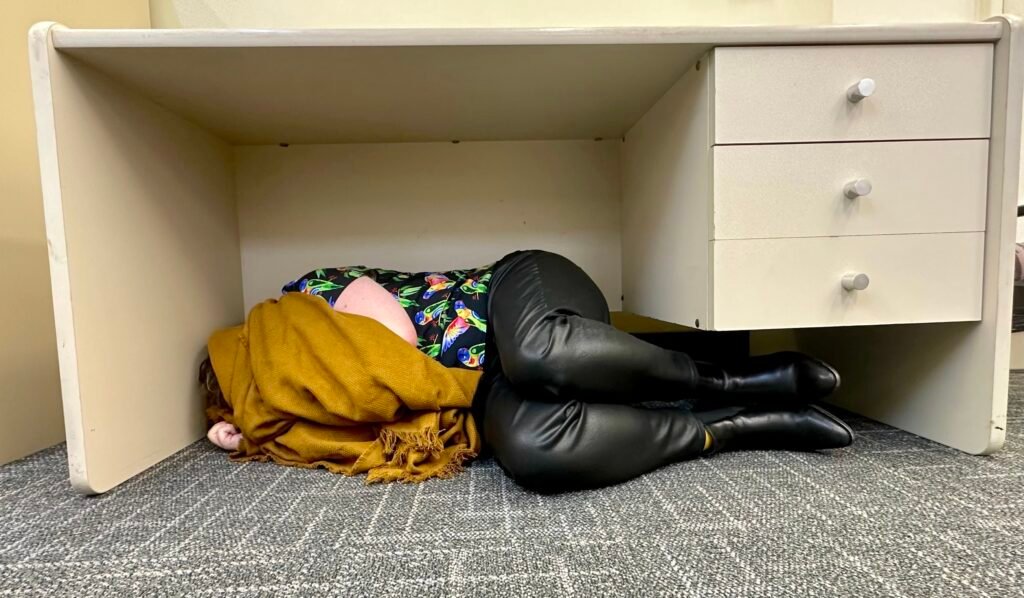

The foundations that make up my house of science has been crumbling down these past few weeks with the influx of new information and ways of thinking.

But with that, it means that I have a chance to rebuild, brick by brick, and be a better science communicator, and potentially more importantly: a better human who displays flexibility, empathy, and curiosity.

This blog entry is an edited assessment piece originally submitted by Kate Holmes for the UWA Master of Science Communication unit – SCOM5311: Science and Society.

We love hearing everyone’s stories of how they got into science communication. What about you? What brought you here? Feel free to share in the comments!

All opinions on this website are representative of individuals and are not representative of The University of Western Australia. The University of Western Australia is not liable for content herein.

1 Comment

[…] Kate’s blog: I Thought I Knew Science. Science Communication Changed That. […]